"As the century of unbounded curiosity, covetous looking and the de-regulation of the gaze, the twentieth has not been the century of the 'image', as is often claimed, but of optics -- and, in particular, of the optical illusion.

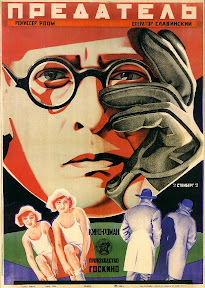

Since pre-1914 days, the imperatives of propaganda (of advertising) and, subsequently, during the long period of Cold War and nuclear deterrence, secuity and iintelligence needs have gradually drawn us into an intolerable situation in which industrial optics have run wildly out of control.

This has produced the new opto-electronic arsenal, which ranges from remote medical detection devices, probing our 'hearts and loins' in real time, to global remote surveillance (from the street-corner camera to the whole panoply of orbital satellites), with the promised emergence of the cyber-circus still to come.

'The cinema involves putting the eye into uniform,' claimed Kafka. What are we to say, then, of this dictatorship exerted for more than half a century by optical hardware which has become omniscient and omnipresent and which, like any totalitarian regime, encourages us to forget we are individuated beings?"

-- Virilio, The Information Bomb, pages 28-29.

I'm interested in the connection Virilio makes with the age of curiosity, because the use of curiosity invokes an image of childishness and wonderment. There is a notion of innocence that comes with this excuse for the gaze, as if this sort of optical technology is a toy for man (Virilio elsewhere in this book talks about 1900s visions of the new century as a vision of blown-up toys for adults). Carelessness comes with curiosity and, just as "curiosity killed the cat" is a horrible saying used to prevent children from sticking their noses into other peoples' business, we can take this age of curiosity as a warning. But perhaps digital technology has made up for this by also making this an "age of consent".

We click 'agree' license and privacy agreements in digital technologies without reading them. We willingly submit details about our lives in the hopes that others will find them interesting (or dateable, or sexy, or intelligent). We post photos of ourselves, tagged with our own full names, searchable by any moderately competent search engine. We allow 'cookies' to show us form-fitted advertisements. Conversely, behind the veil of the screen, we turn and look at all these things in other people. We can browse profiles on dating or social networking sites, look at pictures of thousands of people we don't know -- and their friends and family -- without feeling like a peeping tom. Have voyeurism and consent allied themselves in digital space? Such a question is totally superficial, but worth thinking about in the sense that we can no longer strictly define what is private and what is public.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment