I'm thinking of doing a "walkthough" writing/blog project that involves streets in San Francisco and the differences between the way I view these streets and the way Google Maps portrays them. What follows is only vaguely related to this idea, but serves as a introduction to my home in the world -- which is off the Street View grid, so to speak.

Bernal Hill is the dominant feature of this neighborhood, as you can clearly see. I live at the tip of the park, if viewed as a triangle. Or, more specifically (and from a different point of view), I live here:

I've edited this map, which is clearly a Google Map, in order to convey the spaces from which the following Street Views were taken. The "views" all point toward a street that, some way or another, eventually takes you to my home. An interesting thing geographically about Bernal Heights is that it is a contained neighborhood on a hill -- Cesar Chavez to the North, Mission to the West, Cortland to the South (though Bernal Heights technically exists south of Cortland as well), and 101/Bayshore to the East. I will represent three of these four views, as Cortland does not have Street Views and any further south is outside my own personal experience of this section of town.

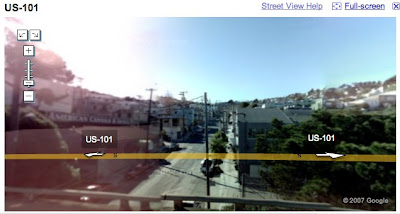

A: 101/Bayshore

This image, taken from a fast-moving highway, is an elevated view of Cortland Ave, which is not documented in the Street View function (fortunately or unfortunately).

B: Cesar Chavez and Precita/Bryant

The buildings in front seem to be blocking the sun. There isn't much light on this street at the moment. Precita Ave, which flows into Bernal Heights and parallels Cesar Chavez a block from this shot, is the quintessential street of a microcommunity: coffee shops, a restaurant, a corner store, a laundry, a cute park. It is the analog of Cortland.

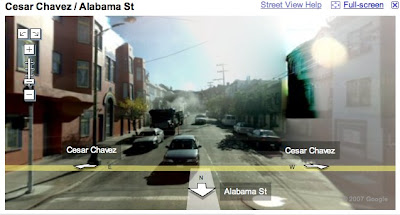

C: Cesar Chavez and Alabama

Alabama is the most direct route to my house. The road rises steeply at the end and drops you off on a ridge that serves the many intricate pathways and tentacle-arms of Bernal streets. This shot is strangely put together; for some reason, the upper floors of a house on the street have been negativized. One wonders what this virtual (mis)representation does to the spirit of the space itself.

D: Cesar Chavez and Folsom

Folsom is a beautiful street lined with trees. This is another direct route to my house; it follows the road that straddles Bernal Hill and approaches the aforementioned ridge from a different direction. (This street will, perhaps, be my first "walkthough")

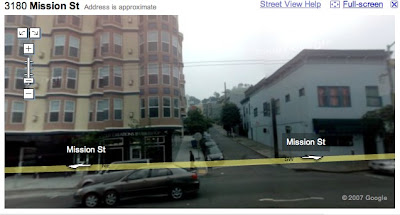

E: Mission and Powers

I never take this route, but it is important to conceive of Bernal Heights as a neighborhood with "options for escape." What I mean is this: Bernal's steep roads are only one line of flight; there are also numerous paths and stairways that allow pedestrians more freedom and creativity in the routes they choose. The point being, I could take Powers and, simply by orienting myself to the hill, could figure out two dozen routes to get home. This option is what is so charming about the neighborhood -- one can always have an interesting walk through Bernal Heights' meandering and hidden paths.

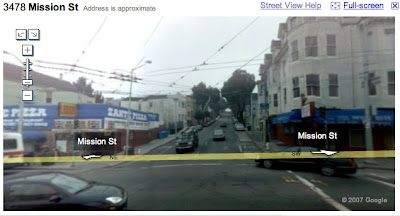

F: Mission and Cortland

Cortland is the lifeblood of Bernal Heights. Though Precita has amenities, Cortland makes Bernal Heights a legitimate neighborhood because it has one of everything: grocer, laundry, bar, restaurant, salon, bookshop, etc, etc. Coming down from Cortland to Mission is one of my most common routes and also one of the most fascinating -- Cortland and Mission are two totally different worlds: Cortland has families, a large lesbian community, and some of the upper crust; Mission is gritty and real, a mix of Latinos and young up-and-ups, and full of the life that makes San Francisco so charming while maintaining its "reality." In some ways, living on a hill is like living in the clouds; moving down the hill grounds my experience of what is real about this place.